Gnosticism

Gnosticism is a term used to describe a diverse group of sects within Christianity that flourished in the second century, before the canon, doctrine and creeds of the Church were solidified. The Gnostics claimed to possess an advanced teaching that had been secretly handed down to them from Jesus and his close circle of disciples.

Some Gnostics offered a radically different view of Jesus’ role and mission than did the churchmen of their day. Because the teachings of the Gnostics challenged the unity of the growing orthodox Church, Church leaders banned, suppressed and almost totally destroyed their scriptures.

Origins

Scholars believe that the origins of Gnosticism may be pre-Christian because the several streams of Gnostic thought reflect Hellenic, Oriental, Iranian and Egyptian philosophic tendencies, including those of Hermes Trismegistus. Among the Christian Gnostics there was a diversity of views and life-styles—some were strictly ascetic; others were accused of being morally licentious. But in general they did share a common belief that the means to salvation was through gnosis, or knowledge. This gnosis was not an intellectual, rational knowing, but a knowledge of one’s self, of God, and of the world—and an understanding of their relationship to each other.

The Gnostics considered themselves the keepers of Christ’s inner teachings, passed down to them by his disciples. They also believed that after Jesus’ resurrection he continued to reveal higher spiritual mysteries—not only to chosen apostles and disciples, but to all who would become quickened to his message and mission. They claimed that this progressive revelation was imparted through visions, dreams or direct communication with the person of Christ.

The Gnostics wrote down these teachings as collections of sayings, parables and proverbs; exhortations or sermons; interpretations of scripture; stories; or dialogues between Jesus and one of the disciples. The dialogues—often written in the name of a disciple or a biblical figure—did not necessarily include the words of the disciple himself but were written, for example, in the spirit of Philip, John or Mary Magdalene as a continuation of their original experience of communion with the Master.

According to what modern scholars have been able to piece together, the atmosphere in which most of these writings had been produced was one of inner conflict and diversity within the Church. Although history has branded the Gnostics as heretics, they were at first fully a part of the emerging Christian community—offering the larger body of Christians a higher interpretation and understanding of the Lord’s teaching.

The suppression of Gnosticism

At a certain point, when the teachings of the Gnostics began to gain popularity, some ecclesiastics decided that the Gnostic version of Christian teaching and practice was not valid or accurate. These churchmen—whose goal was to consolidate authority and stabilize Christian tradition into a unified and codified set of beliefs—denounced the Gnostic writings as blasphemous forgeries and challenged them in lengthy refutations.[1]

By the fourth century, the ecclesiastical leadership had gained enough power to override the Gnostic alternative: they expelled the Gnostics from the Church as heretics and burned their works. These measures were largely successful; very little of the prolific literature produced by the Gnostics has survived to the present. Until the late nineteenth century, we had to depend solely on secondhand reports of Gnostic teachings preserved in the writings of their enemies.

Gnostic texts

The first two original Gnostic manuscripts (Codex Askewianus and Codex Brucianus) were actually acquired by two British collectors in the eighteenth century, but these rare and precious documents remained untranslated—the first for about eighty years and the second for a hundred and twenty years.

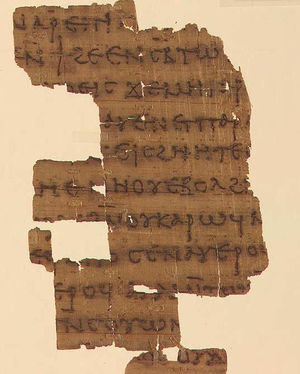

Some of the lost teachings of the Gnostics were discovered in 1945 when an Arab peasant accidentally discovered and broke open an earthenware jar containing thirteen papyrus books bound in leather. These ancient manuscripts, representing fifty-two individual texts (almost all of them previously unknown), were discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt—a village located about sixty miles north of Luxor, Egypt, along the Nile River. They were Coptic translations made in about A.D. 350 from original Greek texts that may date as far back as the first or early second century. Some scholars have speculated that a monk from a nearby monastery hid the banned Gnostic manuscripts in the jar around A.D. 400 to prevent them from being destroyed.

Gnostic beliefs

Although in one sense the aim of the Gnostic was gnosis, or knowledge, we gain a higher understanding of where their sights were set from one of the first Gnostic translators and authorities, G. R. S. Mead. Mead explains that

... one of [the Gnostics’] earliest existing documents expressly declares that Gnosis is not the end—it is the beginning of the path. The end is God. And hence the Gnostics would be those who used the Gnosis as the means to set their feet upon the Way to God.... They strove for the knowledge of God, the science of realities, the Gnosis of the things-that-are; wisdom was their goal; the holy things of life their study.[2]

Third-century father Hippolytus wrote that the Gnostic’s desire was “no more to come into being.” In other words, their goal was freedom from the round of rebirth.

The Gnostics yearned to transcend this transitory world of darkness and ascend back to their native home of light. John wrote in his first epistle: “And we know that we are of God, and the whole world lieth in wickedness.” That does not mean that the Gnostics did not see the beauty of God in this life. It doesn’t mean that they were not happy and joyful people. This is a description of samsara, the veils of illusion that are described in the ancient texts of India. Illusion, then, becomes the play of the Divine Mother whereby we are tested.

“Gold in the mud”

This juxtaposition of the elements of light and darkness is captured in a fundamental Gnostic image—“gold in the mud.” The Greek Church Father Irenaeus left us a record of what the Gnostics meant by this symbol:

Gold, when submersed in filth, loses not on that account its beauty, but retains its own native qualities, the filth having no power to injure the gold.[3]

Professor Werner Foerster explains in his book Gnosis that

... the image of the “gold” implies that the “self” in man [the Real Self] to which it alludes belongs to the sphere of God. Perhaps the gold must yet be purified, the divine element has still to be trained, but the end is certain: the sphere of the divine. The mud is that of the world: it is first of all the body, which with its sensual desires drags man down and holds the “I” in thrall. Thus we frequently hear in Gnosis the admonition to free oneself from the “passions.”[4]

In the Gnostic work entitled The First Apocalypse of James, James the Just says to Jesus:

You descended into a great ignorance, but you have not been defiled by anything in it. For you descended into a great mindlessness, and your recollection remained. You walked in mud, and your garments were not soiled, and you have not been buried in their filth, and you have not been caught.[5]

The theme of the divine origin of the soul is echoed throughout Gnostic literature. Greek theologian Clement of Alexandria quotes the 2nd-century Gnostic poet and teacher Valentinus as saying in a homily:

You are originally immortal and children of eternal life, and you have willed to distribute death among you that you might consume and destroy it.

The state of forgetfullness

The Gnostics believed that it is the nature of the soul “stuck in the mud” of this world to forget her divine origin. They described this state as sleepfulness, drunkenness, or ignorance. What, then, will awaken the soul? It is “the call.”

Werner Foerster says that the Gnostics taught that

... the “call” reaches man neither in rational thought nor in an experience which eliminates thought. Man feels that he is encountered by something which already lies within him, although admittedly entombed. It is nothing new, but rather the old which only needs to be called to mind. It is like a note sounded at a distance [that one hears with the inner ear] which strikes an echoing chord in his heart.[6]

In Gnostic theology, the instrument of the call usually comes in the figure of a redeemer. In Christian Gnosticism it is Jesus who sounds the call and brings the liberating power of gnosis. This concept is also found in the New Testament, which records Jesus as saying: “the Son of man is come to seek and to save that which was lost.”[7] “My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me.”[8]

The Gospel of Truth describes the impelling power of the call as well as the power of gnosis to break the pall of ignorance that holds the soul in its grips:

If one has knowledge, he is from above. If he is called, he hears, he answers, and he turns to him who is calling him, and ascends to him. He knows in what manner he is called. Having knowledge, he does the will of the one who called him; he wishes to be pleasing to him; he receives rest.

He who is to have knowledge in this manner knows where he comes from and where he is going. When the Father is known, from that moment on the deficiency will no longer exist. As with the ignorance of a person, when he comes to have knowledge his ignorance vanishes of itself, as the darkness vanishes when light appears, so also the deficiency vanishes in the perfection. It is within Unity that each one will attain himself; within knowledge he will purify himself from multiplicity into Unity, consuming matter within himself like fire, and darkness by light, death by life.[9]

Orthodoxy vs. Gnositicism

Why were the Gnostics such a threat to the orthodox Church? The independent, free-thinking spirit of the Gnostics challenged the very structure and definition of the Church. The orthodox demanded allegiance to the Church’s creed, rituals, scriptures and clergy. They claimed that God was accessible only through the mediation of the presbyters and bishops; but the Gnostics believed that they had direct access to the Living Christ through the Divine Spark within and did not need a mediator in the person of a bishop.

Rather than the redeeming power of gnosis, Christian opponents of the Gnostics emphasized faith in scripture and unquestioning acceptance of the “divine mysteries.” Tertullian, a Latin Father of the Church, named “thirst of knowledge” in a list of vices. According to Ireneaus and other Church leaders, the criteria for membership in the Church were “visible and simple signs.” “Are you baptized? Do you believe in the creed? Do you obey the bishops?” Gnostic Christians, however, often insisted on the criterion of spiritual maturity.

Summarizing the Gnostic viewpoint on the issue of knowledge over blind faith, Elaine Pagels writes in The Gnostic Gospels:

Uninitiated Christians ... believe in Christ as the one who would save them from sin, and who they believe had risen bodily from the dead: they accepted him by faith, but without understanding the mystery of his nature—or their own. But those who had gone on to receive gnosis had come to recognize Christ as the one sent from the Father of Truth, whose coming revealed to them that their own nature was identical with his—and with God’s.[10]

The Gospel of Philip describes the process of transformation and calls the one who has achieved gnosis “no longer a Christian but a Christ”:

You saw something of that place and you became those things. You saw the Spirit, you became spirit. You saw Christ, you became Christ. You saw the Father, you shall become Father. So in this place you see everything and do not see yourself, but in that place you do see yourself—and what you see you shall become.

“The claim of the Gnostics,” wrote G. R. S. Mead in Fragments of a Faith Forgotten, “was that a man might so perfect himself that he became a conscious worker with the Logos; all those who did so became ‘Christs,’ and as such were Saviours.”[11]

Significance

The ascended lady master Thérèse of Lisieux comments on the significance of the teachings of the Gnostics:

The Gnosticism that has been discovered in this “library in a jar” at Nag Hammadi in 1945 is certainly not the final word, is certainly not the perfected doctrine, but the elements within it reveal clearly that which was banned as heresy by the Church Fathers; and by their banning of this true teaching of Jesus, they have denied our Lord’s doctrine to all the faithful these seventeen hundred years or more.

Know, then, beloved, that Christ has indeed long ago been put out of this Church and that Christ resides only in the pure hearts of those who are within it, and some of these pure hearts have risen to the position of pope and high office and some have been the humble of no particular stature. Therefore they in their hearts of fire rather than through an organization or a doctrine have kept alive the true Presence of Jesus [on earth and, coincidentally, within the Church].[12]

Sources

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Kabbalah: Key to Your Inner Power, chapters 2 and 3.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet with Erin L. Prophet, Reincarnation: The Missing Link in Christianity.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, April 16, 1987.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, May 28, 1987.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, July 12, 1987.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, February 14, 1988.

- ↑ These refutations began toward the close of the first century and continued through the second century. Among their authors were Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Hippolytus. These refutations were directed against all the Christian Gnostic sects and against the work of many of the earliest Christian theologians, including Valentinus, Basilides, Heracleon, Ptolemy and others.—Ed.

- ↑ G. R. S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten (New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960), p. 32.

- ↑ Irenaeus, Against Heresies, in Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., The Ante-Nicene Fathers, American reprint of the Edinburgh ed., 9 vols. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1981), 1:324.

- ↑ Werner Foerster, Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic Texts, 2 vols., trans. R. McL. Wilson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 1:5.

- ↑ James M. Robinson, The Nag Hammadi Library in English (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988), pp. 263–64.

- ↑ Werner Foerster, Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic Texts, 2 vols., trans. R. McL. Wilson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 1:2.

- ↑ Matt. 18:11; Luke 19:10.

- ↑ John 10:1–16.

- ↑ The Gospel of Truth 22, 24, 25, in Marvin Meyer, The Gnostic Gospels of Jesus: The Definitive Collection of Mystical Gospels and Secret Books about Jesus of Nazareth (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005), pp. 99, 101.

- ↑ Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), p. 116.

- ↑ G. R. S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten (New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960), p. 176.

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux, Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 31, no. 39.