Gandhi

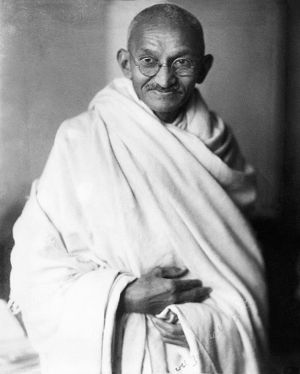

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948) was a Hindu nationalist and spiritual leader. He was called Mahatma (“great-souled”) and regarded as the father of independent India.

Early life

Gandhi was born in Porbandar province on October 2, 1869, the youngest son of orthodox Hindus Karamchand and Putlibai Gandhi.

His father had followed the family tradition of government service as prime minister of Porbandar province, one of the myriad tiny princely states of India, located in west central India on the Arabian Sea.

Following the Eastern belief that holiness comes from renunciation, his mother would set herself very strict penances and disciplines and delight in fulfilling them.

Taking nothing for granted, young Mohan determined to experiment on his own. Some of his experiments were a success. Others showed that the evolving Mahatma had his share of human frailties.

He became infatuated with the practice of smoking. Like many children today, he needed money to support this habit and began stealing a little here, a little there from both servants and siblings.

Mortified at his ineptness at sports and gymnastics, he allowed himself to be convinced by a more agile friend, Sheik Mehtab, to eat meat—a practice abhorred by all Hindus and especially by his family’s Vaishnava sect.

Gandhi’s friend led him to believe that meat-eating would make him “strong and daring,” and he recalls seeing it as a means to free his people from the British. For, as all his school friends knew: “Behold the mighty Englishman / He rules the Indian small, / Because being a meat-eater / He is five cubits tall.” So he arranged a rendezvous with Sheik in a lonely spot where they cooked and ate a goat.

Although at first he found meat revolting, he soon grew to like it and surreptitiously ate it for a year. He discontinued the practice because he felt great guilt in lying to his parents, but resolved to continue when his parents were dead and he would be free to do so as he liked.

Yet the only report that we have of his faults is by his own pen—a pen that treats with utmost severity the slightest transgressions. Gandhi made sure that we would all know his sins. And in knowing them, that we would be unafraid to look at our own and thereby arrest the temptation of making him or ourselves into gods.

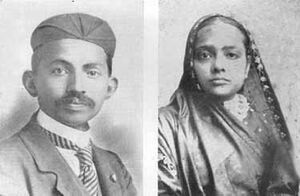

Marriage

Mohandas faced stern challenges from the start. According to Indian tradition, the parents of Mohandas and Kasturbai arranged their marriage when they were both thirteen. All too early, they came face-to-face with the desires of the flesh.

Bound by karma and strict rules of marriage, they lived in his parents’ house except for intervals when as custom dictated she stayed with her parents. Mohandas loved “playing the husband” and records his bitter jealousy and inordinate restrictions upon his wife. He would refuse to allow her to go out, even to play, without his permission. They had many prolonged and violent quarrels on the subject.

Instead of eyeing himself objectively—chalking up the experience to youthful folly—he heaped shame and guilt upon himself. And instead of making excuses, he sought a solution and in later years became one of the original campaigners against both child marriages and the oppression of women.

Writing his autobiography at the age of fifty-six, he looked back upon his early married life and was unduly harsh with himself. His mortification sprung from what he saw as an inordinate obsession.

His consternation with his sexual desire reached its height on the night of his father’s death. Eager to go to Kasturbai, he accepted his uncle’s offer to relieve him of massaging his dying father. Five minutes after he left, a servant knocked at the door telling him, “Father is no more.” He recalled: “If animal passion had not blinded me, I should have been spared the torture of separation from my father during his last moments.... He would have died in my arms.... The shame ... was this shame of my carnal desire even at the critical hour of my father’s death.”[1]

In retrospect, instead of seeing in himself the impulses of a normal teenager, he saw a striving soul diverted from its quest by confrontation with married life. But in the ancient tradition of the saints of both Occident and Orient, he viewed his fleshly nature as an obstacle to be surmounted in the continuing battle to control the senses.

Disillusionment with religion

His parents’ example of devotion notwithstanding, Mohan became disillusioned with religion at an early age. He saw the caste problems, the dominant and rapacious Hindu priests, the oppression of women, and the fact that one-fifth of India—the untouchables—were treated as less than human, and he knew that there must be a better way. He began to “incline somewhat towards atheism.”[2]

But far from “turning him off” to religion, Mohandas’ anti-religious sentiments quickened his interest and he listened attentively to his father’s frequent discussions with Muslim and Parsi friends on the differences between their faiths and Hinduism, seeking meaning beyond tradition and ritual, selecting a bouquet of ideas appealing to his soul. At that time, he wrote, “one thing took deep root in me—the conviction that morality is the basis of things and that truth is the substance of all morality.”[3]

From then on, “Truth became my sole objective. It began to grow in magnitude every day, and my definition of it also has been ever widening.”[4] This pursuit of Truth lasted a lifetime, and took him to diverse places.

Study of law

In the year 1887, even though Kasturbai had just presented him with their first son, he determined to leave his wife and child and take his search to England and law school. His mother refused to let him go until he vowed to abstain from wine, women, and meat. Acquiescing, Mohandas exuberantly donned European dress and set out for the West.

Although he didn’t really agree with his mother’s restrictions, a vow was a vow. And for his first few months in London (until he found a vegetarian restaurant), he lived almost solely on boiled spinach and bread. The few times he did eat in typical London restaurants were trying experiences. His Indian friends thought that he was ridiculous and refused to take him out to eat because he would make the waiter recite the ingredients of each dish!

Then, experimenting with emulation, Mohandas pursued the life of an English gentleman—studying dancing, French, elocution, and violin. But finding that this life did not mesh with his internal Truth, he soon began to simplify, moving to cheaper quarters and cooking his own food.

Since his “curriculum of study was easy, barristers being humorously known as ‘dinner barristers’,”[5] he had plenty of spare time. He studied the classics and became fluent in English and Latin. And in the midst of these secular studies, religion unexpectedly reentered his life.

In 1889, a friend convinced him to read the Bhagavad-gita, the sacred book of Hinduism, which he had never examined before. It made a lasting impact. “The book struck me as one of priceless worth. The impression has ever since been growing on me with the result that I regard it today as the book par excellence for the knowledge of Truth.”[6]

He was also persuaded to read the Bible. The Old Testament did not interest him much, but he was thrilled by the New—especially the Sermon on the Mount. He embraced it as an expression of that which he had known in his heart since birth. Not only did he find it to be interchangeable with the words of the Gita, but also it became the spiritual basis for his revolutionary philosophy.

Gandhi, previously disillusioned by the narrowmindedness of a Christian missionary, began to reassess his former views. As he saw “devout souls kneeling before the Virgin,” his tolerance for Christianity increased. And when he realized that they “worshipped not stone, but the divinity of which it was symbolic,”[7] he was transported. He had also learned a lot about the British and, like Moses, his study of the conquerors’ laws and customs was of inestimable value in the liberation of his people.

But Mohandas’ chief gain in England did not come from his education. Rather, he gained by his increased introspection. No longer the confused adolescent, he was now of the growing opinion “that renunciation was the highest form of religion.”[8] Easily passing the exams at the end of three years’ schooling, Gandhi was called to the bar and duly enrolled in the High Court on June 11, 1891. The next day he sailed for home.

Return to India

Upon arrival in India, he was devastated by the news that his mother had died some weeks before his return. Bereft of her support, Gandhi knew he had to make it on his own. And he soon discovered that a British degree was no ticket to success.

Gandhi found himself completely helpless in the courtroom. His law career sputtered and never really got started. But Gandhi knew that he did not want to be counted among the typical Indian barristers who, though in slavish imitation of the British ruling class, loudly bemoaned their fate as a suppressed race.

As fate would have it, in 1893 he received an offer to act as an English translator and aide to a firm conducting a case in South Africa. For him, it was a “tempting opportunity,” and, with no inkling of the struggles that awaited him, he took leave of his wife and set out.

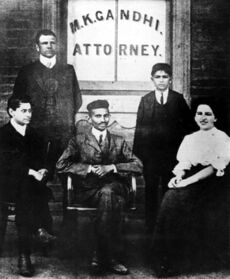

Work in South Africa

The brutal treatment of Indians in South Africa came as a rude surprise. Gandhi was thrashed and continually insulted by Europeans. The most mild insults were “sammy” (a corruption of swami) and “coolie.” Shocked, intimidated, and disgusted, he wanted to return home. “I might, on the one hand, free myself from my contract,” he later wrote. But, matters weren’t that simple. Gandhi was a man of principle. “On the other hand,” he resumed, “I might bear all the hardships and fulfill my engagement.”[9]

“While I was still undecided, I was pushed out of the train one night by a European police constable at Maritzburg.” Sitting in the waiting room, shivering and meditating through the night, “doubt took possession of my mind.” But principle triumphed. “Late that night I came to the conclusion that to run away back to India would be a cowardly affair. I must accomplish what I had undertaken.”[10]

At the outset, things did not look promising. But Gandhi’s reverence for Truth gave him strength to persevere where few had the courage. For Gandhi, South Africa was a laboratory, a proving ground, and a crucible where the evolving soul discovered the spiritual and soul principles that would shape the mature Mahatma’s life. He settled in the mining province of the Transvaal and spent the next nineteen years of his life fighting in the cause of equal rights for Indians in South Africa.

He soon gained some degree of success and the reputation as the most honest lawyer in town. But that was far from satisfying him. "The problem of further simplifying my life and of doing some concrete act of service to my fellow-men [was] constantly agitating me.”[11]

Soon Gandhi’s religious striving reached its peak. Sampling creeds and doctrines of both East and West, he read avidly: the Koran, The New Interpretation of the Bible, and was “overwhelmed” by Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You. Still, he wrote, “I could not accept Christianity either as a perfect, or the greatest religion, neither was I then convinced of Hinduism being such.”[12]

In 1896, Gandhi returned to India for six months to fetch his wife and family. Once settled in South Africa, “I found myself entirely absorbed in the service of the community. The reason behind it was my desire for self-realization. I had made the religion of service my own.”[13] He even nursed a leper with his own hands.

Gandhi sought simplicity and “iron discipline” in his personal life as a means to self-realization. And he was amazingly one-pointed in his quest. He reduced household expenses to a minimum, gave up many European habits, started cutting his own hair and doing his own laundry. His first trials resulted in a scorched collar and ruined hair. When his fellow barristers ridiculed him, he merely expressed his gratitude at being able to give them some fun.

As Gandhi searched for God as the hub of his life, he himself was moving toward center. As he sought service to his fellowman, the lines of force began to form a radial pattern around the one who cared most for the disenfranchised.

When Gandhi made a visit to India in 1901 to attend a session of the Indian National Congress, he noticed several things to which he could not reconcile himself.

The congressional delegates were in the habit of relieving themselves wherever they pleased, expecting a scavenger to clean up after them. The latrines were an abomination. How, Gandhi wondered, could these men expect to achieve Indian rights when they themselves were grossly irresponsible? Still pondering the matter, he got a broom and began to clean up the mess himself, as he could find no one to “share the honor” with him.

He also realized that although the delegates were fond of making overlong speeches full of high-sounding phrases, they could neither touch the bulk of the 300 million Indians nor convince their English rulers of their responsibility by merely awing each other. Seeking an answer, Gandhi once again set sail for South Africa.

Realizing that some of the Europeans’ criticisms of the Indians—they called them lazy, shiftless, and slovenly—were well-founded, and seeking new ways to serve, Gandhi formed a volunteer Indian ambulance corps during the Boer War (1899–1902), although his sympathies were on the side of the Boers. For, according to his inner standard of Truth, he must support the British Empire’s endeavors in order to claim citizenship.

The Europeans were amazed to see the Indians taking part, for before this they had thought all Indians to be “cowardly and self-serving.” During his years in South Africa, he also served as a nurse during a plague and tended the wounds of the Zulus in the Zulu rebellion, since the British ambulance corps balked at the task.

Keeping his own surroundings immaculate, Gandhi also began vigorously campaigning for sanitation among his co-workers. Cleanliness became an integral part of his philosophy. His willingness to correct Indian faults gained the esteem of the British, who saw that “though I had made it my business to ventilate grievances and press for rights, I was no less keen and insistent upon self-purification.”[14]

In 1903, a friend lent Gandhi a copy of John Ruskin’s Unto This Last, advocating the simplified life and an economic system that would be equitable to all. Ruskin’s ideas inspired Gandhi to buy a hundred-acre farm near Phoenix, Natal, South Africa. Giving up his now lucrative law profession, he experimented with equal participation in all levels of the community. In doing so, he was challenging apartheid not only in South Africa but in India as well, where the caste system had institutionalized a servant class.

Gandhi, although a high-caste Hindu, would never ask any man to do anything which he himself had not done. Spending his time “working for the working men,” tending to crops and livestock, collecting garbage and cleaning latrines, Gandhi was able to deal a specific and calculated blow to both Hindu and European prejudices. Other Indians soon to be his followers would have had a hard time accepting these ideas had Gandhi not proved them in action. He was a leader by calling, yet always a follower of Truth wherever she would lead him.

Brahmacharya vow

Gandhi’s desire to reach God had mounted to such heights that he began to think seriously of taking the brahmacharya vow. Brahmacharya means, literally, “conduct that leads one to God.” Its technical meaning is self-restraint, particularly in regard to sex. This vow was a tradition among holy men of the East. Gandhi later broadened his definition to include control of the senses in thought, word, and deed. His consideration of brahmacharya began as a continuation of his desire to control his passions. He believed that his wife should not always be a slave to his lusts.

Whether following the ideal of the Eastern ascetic or the inner necessity for sacrifice to achieve his goals, once convinced of his course of action Gandhi was determined to overcome. So, with the agreement of Kasturbai, he twice attempted to become celibate. But he failed both times. Then in 1906, at the age of thirty-seven, he took a vow of complete renunciation, because

I realized that a vow, far from closing the door to real freedom, opened it.... I clearly saw that one aspiring to serve humanity with his whole soul could not do without it.... In a word, I could not live both after the flesh and the spirit.”[15]

Gandhi never broke his vow. Years later, he realized that brahmacharya was impossible to attain by mere human effort. It was only by acknowledging the power of God within that he could control his senses.

His was a very personal vow. He never requested his followers to take it. Gandhi saw his life as simply a segment of Life in its totality which he could not continue to be a part of unless he could merge with it through self-mastery. But brahmacharya was not without its trials. “Let no one believe that it was an easy thing for me. Even when I am past fifty-six years, I realize how hard a thing it is. Every day I realize more and more that it is like walking on the sword’s edge, and I see every moment the necessity for eternal vigilance.”[16]

He experimented much with the correct food, exercise, rest, and various disciplines for the brahmachari (one who practices brahmacharya), but in all of his life, he never once repined once he had taken his final vow. He also attributed the evolution of his philosophy of nonviolence to the fact that he had taken the brahmacharya vow.

Experiments with civil disobedience

Gandhi’s lifelong experiment in civil disobedience began in South Africa—an experiment which echoed around the world and still reverberates nearly eighty years later. “I can now see,” Gandhi later wrote, “that all the principal events of my life ... were secretly preparing me for it.”[17]

Gandhi gave birth to his revolution, raising his consciousness to the point at which true spirituality could be applied to politics—and that without compromise. He discovered out of the measure of his own heart the inner standard of Love to be the most thoroughly practical means of overcoming evil.

It was the New Testament which really awakened me to the rightness and value of passive resistance. When I read in the Sermon on the Mount such passages as “Resist not him that is evil but whosoever smiteth thee on thy right cheek turn to him the other also.”... I was simply overjoyed, and found my own opinion confirmed where I least expected it.[18]

But Gandhi did away with the term passive resistance and searched for an Indian equivalent that would better translate Christ’s example to his people. “Satya (Truth) implies Love: and Agraha (Firmness) serves as a synonym for Force. So I began to call the Indian movement ‘Satyagraha.’ By this I meant the Force which is born of Truth and Love.”[19]

Gandhi wrote:

The beauty of this method is that it comes up to oneself; one has not to go out in search for it.... God Himself plans the campaign and conducts battles. It can be waged only in the name of God. Only when the combatant feels quite helpless—only when the combatant finds utter darkness all around him, only then God comes to the rescue.[20]

Gandhi knew that Jesus Christ had been called the original passive resister, but he saw him as the original Satyagrahi.

Satyagraha’s first trial on a grand scale came in South Africa when, on July 31, 1907, the Asiatic Registration Act was passed to restrict all Indians. “It was better to die,” Gandhi wrote, “than to submit to such a law”[21] that required each Indian to carry a pass at all times and which could be requested of him, even in his own house.

The Indian community was determined to fight back. Gandhi gave them a weapon which could be used by all. The Satyagrahis courted jail. Their method was to disobey the offending law until they received a response—any response—but they vowed never to use any form of violence.

Gandhi was able to weld 13,000 Indians into a single force. One of the first to be arrested, he spent many months in jail in Johannesburg, sometimes in hard labor and other times in solitary confinement. Nearly all of the nonviolent warriors endured the beatings, arrests, jail sentences, insufficient food, and sentences of hard labor “with a smile on their face.... They did not know what it was to be beaten.”[22]

Critics of Gandhi call his philosophy masochistic because people sustained beatings without resisting in the Satyagraha campaigns. Yet how many more die in war without any sense of self-esteem, without having taken a stand for a moral principle or made the ultimate sacrifice for the cause of Truth. Satyagraha is the strategy of a mastermind (his Master’s mind) who knew the enemy well yet held the salvation and soul integrity of his followers as paramount.

On January 30, 1908, Gandhi was taken from his jail cell to see General Smuts—the representative of the British government in South Africa. Smuts promised that if the Indians would register for passes, he would repeal the Asiatic Ordinance.

Taking Smuts at his word, Gandhi convinced the Satyagrahis to register and insisted upon being the first. On his way, he was almost beaten to death by a hostile Pathan Indian who believed him to be betraying the cause. Broken and bleeding and barely conscious, he still insisted upon signing the registration card.

But even after this show of good faith, Smuts double-crossed him. Instead of repealing the law, Smuts introduced more legislation against the community. Though chagrined, Gandhi realized that:

A Satyagrahi bids good-bye for ever to fear. He is therefore never afraid of trusting his opponent. Even if the opponent plays him false twenty times, the Satyagrahi is ready to trust him for the twenty-first time; for an implicit trust in human nature is his creed.[23]

Gandhi’s trust paid off. Smuts’ intrigue backfired and generated sympathy for the Indians in the European community, and Gandhi continued the fight against the Ordinance. On August 16, 1908, he led 2,000 in burning their registration cards at the Hamidia Mosque in Johannesburg. One British reporter likened it to the Boston Tea Party.

The quality of striving exhibited by the troops was rewarded when, after seven years of persistence, an Indian Relief Bill was passed and most of the Indians’ demands were granted.

After Gandhi left South Africa, the Satyagrahis gradually gave up the fight. Some consider Gandhi a failure because of the backsliding of South Africa after his departure. They grant that Satyagraha worked in India but do not see it as a relevant philosophy today.

South African specialist Carol Thompson, a professor at the University of Southern California, believes that “the native Zulus in South Africa later used nonviolence for fifty years against the whites. I think fifty years is a long enough trial period.”

Possibly anticipating such criticism, Gandhi wrote:

When one considers the painful contrast between the happy ending of the Satyagraha struggle and the present condition of Indians in South Africa, one feels for a moment as if all this suffering had gone for nothing, or is inclined to question the efficacy of Satyagraha as a solvent of the problems of mankind. But let us consider this point for a little while.

There is a law of nature that a thing can be retained by the same means by which it has been acquired. A thing acquired by violence can be retained by violence alone, while one acquired by truth can be retained by truth alone. The Indians in South Africa, therefore, can ensure their safety today if they can wield the weapon of Satyagraha. There are no such miraculous properties in Satyagraha that a thing acquired by truth could be retained even if truth were given up.[24]

It seems that the fault is not in the weapon, but rather in the warriors.

In July of 1914, their champion returned to India, leaving the schoolroom of South Africa where he had learned life’s most important lessons. Tempered in the fire of service, armed with the force of Truth, he was now ready for his calling, soon to be revealed in its full magnitude.

Social reform in India

Gandhi began by serving the people. If anyone was starving, oppressed, or helpless, Gandhi would take up the struggle. Fighting famine, injustice, and untouchability, he moved up and down the country, exhorting all men to be brothers. Wherever he went, he was not content merely to advocate political reform, but he promoted his entire way of life unceasingly.

While working for peasant emancipation in Champaran, he also opened six primary schools, gave the local villagers lessons in sanitation and waste-disposal, succeeded in changing the diet of the vakils assisting him, set up medical relief centers, and even lobbied for cow protection. However, in most cases, social reforms lasted as long as he was there to oversee them. Since many of his programs were strictly voluntary, only a few were willing to give up everything to serve the people.

The struggle continued and, faced with a seemingly irreconcilable situation, Gandhi’s inner voice revealed to him another powerful strategic weapon to be used in the practice of Satyagraha. It came to him as he was assisting some mill strikers in Ahmedabad. They began to get tired of their cause and were ready to capitulate.

One morning ... unbidden and all by themselves the words came to my lips: “Unless the strikers rally,” I declared to the meeting, “and continue the strike till a settlement is reached, or till they leave the mills altogether I will not touch any food”...

The hearts of the mill-owners were touched, and they set about discovering some means for a settlement.[25]

The difference between Gandhi and some hunger strikers of recent years is that Gandhi was respected and loved by both sides of the dispute. Gandhi used fasting several times over the years, always as a last resort—once to stop the Indians from killing the British, and again to stop Hindus and Muslims from killing each other. It always accomplished its end.

Ever the devoted scientist, Gandhiji (ji is a term of respect and endearment) was continually developing and refining his sense of Truth. At one time, he became very ill, partly due to his experiments in diet (he was living mainly on nut-butter and lemons). No doctor could help him because he refused to take medicine or injections of any kind. Even beef broth and milk were out of the question because he had taken vows against them. He was at death’s door.

Finally a doctor said that he could cure him if he would agree to drink goat’s milk. This meant breaking a vow and thus compromising Truth.

I agreed to take goat’s milk. The will to live proved stronger than the devotion to truth.... But I cannot yet free myself from that subtlest of temptations, the desire to serve, which still holds me.[26]

The struggle for Indian independence

After his recovery, Gandhiji resolved to devote his time to the cause of Swaraj (home rule). He began promoting Satyagraha emphasizing noncooperation throughout India, discovering ever-new means of putting them into action.

Gandhi’s inner sense of Truth soon revealed to him the need for a self-sufficient India. In 1921, he led the nation in a new kind of trade war—burning and boycotting their British cloth. He soon reinstituted the art of spinning, not because he saw khadi (homespun) as superior in quality to Lancashire cloth, but because to him it was a means of ending British monopoly and control of the Indians. Furthermore, it would solve the problem of the multitude of half-starved, semi-idle peasants and beggars.

The wearing of khadi cloth became a symbol of the revolution. Charkas (spinning wheels) were everywhere and Gandhiji sometimes meditated for hours upon the rotation of the wheel, planning his campaigns. He carried his charka with him at all times—spinning before ambassadors and conducting spinning classes as he went. One Englishman recalls that even British college students in England were wearing khadi cloth.

After a few successful trials of Satyagraha, he issued a call for widespread civil disobedience for April 18, 1919. But the nation could not control itself. Nonviolence quickly deteriorated into riots when British mounted police accosted the crowds of passive demonstrators. The Indians retaliated brutally, igniting widespread atrocities and massacres on both sides, especially in the northern province of the Punjab.

“I had committed a grave error,” Gandhi wrote, “in calling upon the people ... to launch upon civil disobedience prematurely, as it now seemed to me.”[27] Taking the blame for his “Himalayan miscalculation,” Gandhi embarked upon a five-day fast. From 1924–27, he held aloof from political activity and devoted himself to a constructive program of Hindu-Muslim amity, removal of untouchability, and popularization of khadi.

After 1927, he again began campaigning for Swaraj—alternating between jail, political activity, protest through fasting, and ashram life. If Gandhi campaigned wholeheartedly for Swaraj, then he campaigned “wholesouledly” for the eradication of untouchability. “Swaraj is a meaningless term, if we desire to keep a fifth of India under perpetual subjugation and deliberately deny to them the fruits of national culture.”[28]

People of all castes flocked to him, worshiping their Mahatma—yet Gandhi had a horror of idolatry. Once he received a report that a temple had been constructed in his honor. He became incensed and demanded that the idol be removed and the building converted to a spinning center.

From March 12 to April 6, 1930, Gandhi led seventy-eight disciples on a 200-mile march to the sea at Dandi to make salt in symbolic protest of British monopoly of salt manufacturing. The populace had learned their lessons and were now model Satyagrahis, delighted at this and every other new means of putting it into action.

Time magazine reported on Gandhi’s campaign in its June 30, 1947, issue. Its cover bore the image of Gandhi with the quote: “I wish to wrestle with the snake.” The snake was the snake of politics that Gandhi grappled with fearlessly. Time observed:

With each fast, each boycott, and each imprisonment (by a British Raj which feared to leave him free, feared even more that he would die on their hands and enrage all India), Gandhi came closer to his goal of a free India. With the same weapons he got in some blows at his favorite social evils—untouchability, liquor, landlord extortions, child marriages, the low status of women.

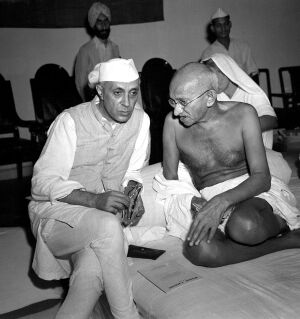

It was much easier, however, for the population of India to accept a campaign for freedom than to accept an overturning of their ancient traditions. Consequently, as World War II and what Time called this “most colossal experiment in world history” drew to a close, fewer and fewer were willing to institute his social reforms. From 1946–47, the British government, represented by Lord Mountbatten, the Indian National Congress, headed by Jawaharlal Nehru and advised by Mohandas Gandhi, and the All-India Muslim League, headed by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, negotiated to find the best possible means for Swaraj.

It was then that Jinnah, until this time Gandhi’s political ally, showed his true colors. It was now, when victory seemed so easily attainable, that Jinnah played his card. Despite Gandhiji’s entreaties, Jinnah refused to agree to a united India because he did not believe Muslims would be treated fairly. Ruthlessly, he gave Gandhi a choice between civil war and two nations. “I do not care how little you give me, so long as you give it to me completely,” he declared. Gandhiji was forced to agree and India was partitioned into two nations—India and Pakistan.

The subsequent mass riots between Hindu and Muslim, interrupted momentarily by Gandhi’s last fast, were among the most sanguinary in history and seemed to be the ultimate defeat of Satyagraha and thus of Gandhi. So when, on January 30, 1948, Gandhi was struck down by a Hindu assassin’s bullet, it was seen as the culmination of his failure.

Perhaps some would cite as his greatest fault his inability to reconcile himself to the belief that anyone could be the relentless embodiment of evil—even to the death of his dreams and his dharma in that frail form. Thus he did not take strong measures against Jinnah. His system had no immediate answer for such a confrontation with the enemy of his life’s mission—except a recess until the next round in the next life when karma as the Law of Love—outplayed in the effects set in motion by his cause—would afford him another opportunity—this time to love and win.

Political philosophy

Mohandas Gandhi is usually thought of as a revolutionary or a saint. But he was also an avant-garde political and economic thinker. Every bit as important as Adam Smith or John Locke, his work constitutes the next step in the evolution of political and economic thought. “He was very forward,” says Romesh Diwan, an economist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. According to Diwan, who has written extensively about Gandhian economics, “He was two hundred years ahead of his time.”

Neither an abstract theoretician nor a codifier, Gandhi’s copious writings on the social and political order are interspersed in the leaves of some eighty volumes of his collected works. But the hub of all of Gandhi’s thought is simple: “God exists.” As a result, man’s sole aim is “to live in truth” and become one with his creator.

This revelation did not prompt Gandhi to withdraw from a corrupt civilization to a Himalayan cave. On the contrary, it catapulted him into the very midst of his people. In fact, his career as a politician was born out of a love of God—the God who walked and worked the earth in the hearts of His people. Gandhi wrote:

Man’s ultimate aim is the realization of God, and all his activities, social, political, religious, have to be guided by the ultimate aim of the vision of God. The immediate service of all human beings becomes a necessary part of the endeavour simply because the only way to find God is to see Him in His creation and be one with it. This can only be done by service of all.[29]

The people, as he found them, were much in need of service. In 1910, it was not in vogue to condemn modern industrial civilization. Yet Gandhi’s critique was scathing—a “soulless system” which was violent, full of inequities, narcissistic and which made “bodily welfare the object of life.”[30]

Gandhi was equally thorough in his indictment of the sinister materialism of both capitalism and communism. “Gandhi was the first thinker to see clearly what was common to European capitalism and Communist Russia,” observed Dr. Raghavan Iyer, a political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “He easily extended his attack on modern civilization, the gospel of material progress, and the glorification of violence, to cover Soviet civilization as well as the capitalist countries.”[31]

However, on close examination, it is apparent that Gandhi was not opposed to machines, technology, wealth, or any other single component of “civilization,” or even all of these factors taken together. What he opposed, as Dr. Iyer points out, was “ruthless mechanization, the Midas-complex and power-mania.”[32] Gandhi feared India would become seduced by transplanted economic exploitation, or worse, debilitating material comforts. He wrote in Hind Swaraj:

It would be folly to assume that an Indian Rockefeller would be better than the American Rockefeller. Impoverished India can become free, but it will be hard for any India made rich through immorality to regain its freedom.[33]

He would have to find new rules and discover a new social order to prevent India from “being ground down, not under the English heel, but under that of modern civilization” which was causing India to turn “away from God.”[34] In both the capitalist and communist worlds, power and wealth—and hence the tendency to exploit—gravitated to the top and concentrated in a few hands in urban centers.

Gandhi’s solution was an obvious one. Turn the whole structure on its head. “Independence must begin at the bottom,”[35] he declared. He would start with the individual as the hub of the village and the village as the hub of society, and build from there.

The spinning wheel permeated one of his few sketches of the future “Gandhian” society in which he described a highly decentralized government of limited powers, where “every village will be a republic or panchayat having full powers.”[36]

He described a self-sufficient society that could maintain its moral priorities and provide a rich enough political and economic life to resist penetration by malignant outside forces. He wrote:

It follows, therefore, that every village has to be self-sustained and capable of managing its affairs even to the extent of defending itself against the whole world. It will be trained and prepared to perish in the attempt to defend itself against any onslaught from without. Thus, ultimately, it is the individual who is the unit....

In this structure composed of innumerable villages, there will be ever-widening, never-ascending circles. Life will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. But it will be an oceanic circle whose centre will be the individual always ready to perish for the village, the latter ready to perish for the circle of villages, till at last the whole becomes one life composed of individuals, never aggressive in their arrogance but ever humble, sharing the majesty of the oceanic circle of which they are integral units.[37]

Some rejected the metaphysical nature of his scheme. Gandhi anticipated his critics: “I may be taunted,” he wrote, “that this is all Utopian and, therefore, not worth a single thought.”[38]

But he believed that it was necessary for the goal of the political order to be lofty, even unreachable, for progress to occur, and countered, “If Euclid’s point, though incapable of being drawn by human agency, has an imperishable value, my picture has its own for mankind to live.”[39]

But if the goal is unreachable in the short run, it lays out a framework for developing nations that when adhered to will enfranchise the people, yield political stability, and produce long-term economic growth without forcing the government to seek outside aid from East or West. In short, with this plan a nation can retain control of its own destiny.

See also

Sources

Heart magazine, Autumn 1983.

- ↑ Mohondas K. Gandhi, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Dover, 1983), p. 26.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 30.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 71.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 59.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 68, 69.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 60.

- ↑ C. F. Andrews, ed., Mahatma Gandhi At Work: His Own Story Continued (Macmillan, 1931), p. 64.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 65.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 97.

- ↑ Experiments with Truth, p. 119.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 139.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 191.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 180–81, 281.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 182–83.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 284.

- ↑ Mahatma Gandhi At Work, p. 374.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 150.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 137.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 288.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 223.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 369.

- ↑ Experiments with Truth, pp. 388, 390.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 411.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 424.

- ↑ Young India, May 25, 1921.

- ↑ Young India, May 25, 1921.

- ↑ Mahatma Gandhi, Louis Fischer, ed., The Essential Gandhi: His Life, Work, and Ideas: An Anthology (Vintage Books, 1962), p. 121.

- ↑ Raghavan N. Iyer, The Moral and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi (Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 34.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 36.

- ↑ Mahatma Gandhi, Hind Swaraj (Delhi: Rajpal & Sons, 2010), p. 76.

- ↑ Iibid., p. 33.

- ↑ Mahatma Gandhi, India of My Dreams (Delhi: Rajpal & Sons, 2008), p. 99.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 100.

- ↑ Ibid.