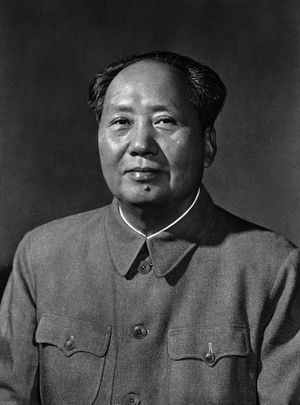

Mao Tse-tung

Mao Tse-tung (Mao Zedong) (1893–1976) was one of the 12 founders of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921 and leader of Chinese Communists from 1935 to his death. So great was his influence that even after his death, Mao remained a key figure in Chinese politics.

Summarizing Mao’s early years as chief of state of the Communist People’s Republic of China, Dr. Richard L. Walker notes in The Human Cost of Communism in China:

Millions were executed in the immediate post-power seizure period in Communist China. Many of the executions took place after mass public trials, in which the assembled crowds, whipped up to a frenzy by planted agitators, called invariably for the death penalty and for no mercy for the accused. During this early period, Mao and his colleagues made no effort to conceal the violent course being followed. On the contrary, the most gruesome and detailed accounts were printed in the Communist press and broadcast over the official radio for the purpose of amplifying the condition of mass terror the trials were clearly intended to induce.[1]

As Mao himself had foretold in 1927 in one of his earliest works, “to put it bluntly, it is necessary to create terror for a while in every rural area.”[2]

There is a broad range of estimates as to the exact number of Chinese who have died at the hand of the Communists; Dr. Walker estimates that the figure was probably close to 50 million. Some of the most brutal campaigns waged by the Communists under Chairman Mao were:

- the Agrarian Reform (1949–52) resulting in the execution of several million landlords;

- invasion and take-over of Tibet (1950), promising Tibetan autonomy but eventually establishing a Chinese military dictatorship that killed hundreds of thousands of Tibetans, confiscated or destroyed monasteries and religious scriptures, stripped the people of their private property, and reorganized the country into peasant associations;

- campaign against counterrevolutionaries (1951–52, 1955), leaving one and a half million dead in the first 12 months;

- purges in business, finance, and industrial circles leading to many executions and suicides (1951–53);

- a vehement liquidation campaign to silence rightist critics following Mao’s “Hundred Flowers” speech inviting intellectuals and others to voice their criticism (1957–58);

- the Great Leap Forward (1958–60), a disastrous attempt to rapidly increase economic development through the formation of large rural communes, in some cases separating families and forcing peasants to adopt a militarized lifestyle;

- the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–69), used by Mao to strike back at pragmatic leaders who had risen to power after his economic failures and to secure a group of successors devoted to his revolutionary ideals—included uncontrolled and violent attacks by radical youth organizations, called the Red Guards, against those who were “taking the capitalist road,” purges of intellectuals who were forced to work in labor camps or were executed, and relocation to the countryside of an estimated 25 million youth, many of whom were assigned to work the land for life; the tearing down of traditional Chinese culture, customs, and religious practices with systematic destruction of libraries, shrines, and art works.

See also

Sources

Archangel Gabriel, Mysteries of the Holy Grail, pp. 322–23.

- ↑ Richard L. Walker, The Human Cost of Communism in China (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971), p. 11.

- ↑ Mao Tse-tung, “Report of an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” in Thomas M. Buoye et al., ed., China: Adapting the Past, Confronting the Future (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Center for Chinese Studies, 2002), p. 88.