Utopia: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "thumb|Illustration for the title page of ''Utopia'', first edition (1516) ''Utopia'' was the principal literary work of Sir Thomas More (1478–...") |

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) (Marked this version for translation) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

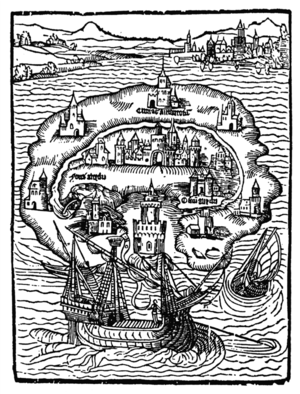

[[File:Insel Utopia.png|thumb|Illustration for the title page of ''Utopia'', first edition (1516)]] | <languages /> | ||

[[File:Insel Utopia.png|thumb|<translate><!--T:1--> Illustration for the title page of ''Utopia'', first edition (1516)</translate>]] | |||

<translate> | |||

<!--T:2--> | |||

''Utopia'' was the principal literary work of Sir [[Thomas More]] (1478–1535), published in 1516, a witty exposé of the superficiality of English life and the flagrant vices of English law. | ''Utopia'' was the principal literary work of Sir [[Thomas More]] (1478–1535), published in 1516, a witty exposé of the superficiality of English life and the flagrant vices of English law. | ||

== Themes == | == Themes == <!--T:3--> | ||

<!--T:4--> | |||

In his masterpiece, More considers what is the best form of government. He describes an imaginary island, the imaginary commonwealth Utopia (meaning “no place”), where people live according to the rule of reason—free from poverty, crime, and injustice. It is an attempt to depict an ideal society, where neighbor lives in harmony with neighbor and nations are of one accord—not under compulsion of manmade law, but under the wand of grace, the holy will of the Most High. | In his masterpiece, More considers what is the best form of government. He describes an imaginary island, the imaginary commonwealth Utopia (meaning “no place”), where people live according to the rule of reason—free from poverty, crime, and injustice. It is an attempt to depict an ideal society, where neighbor lives in harmony with neighbor and nations are of one accord—not under compulsion of manmade law, but under the wand of grace, the holy will of the Most High. | ||

== Influence == | == Influence == <!--T:5--> | ||

<!--T:6--> | |||

''Utopia'' is many things to many people. Historians have taken Utopia as a blueprint for British imperialism, humanists as a manifesto for total reform of the Christian renaissance, and literary critics as a work of a noncommitted intellectual. | ''Utopia'' is many things to many people. Historians have taken Utopia as a blueprint for British imperialism, humanists as a manifesto for total reform of the Christian renaissance, and literary critics as a work of a noncommitted intellectual. | ||

<!--T:7--> | |||

In it More describes an ideal society where all property is held in common and food is distributed at public markets and common dining halls. With its sweeping condemnation of all private property, ''Utopia'' influenced early Socialist thinkers. Karl Kautsky, the German Socialist theoretician, saw ''Utopia'' “as a vision of the socialist society of the future”<ref>John Anthony Scott, Introduction to ''Utopia'', trans. Peter K. Marshall (New York: Washington Square Press, 1965), p. xvii.</ref> and hailed More as the father of the Bolshevik Revolution. | In it More describes an ideal society where all property is held in common and food is distributed at public markets and common dining halls. With its sweeping condemnation of all private property, ''Utopia'' influenced early Socialist thinkers. Karl Kautsky, the German Socialist theoretician, saw ''Utopia'' “as a vision of the socialist society of the future”<ref>John Anthony Scott, Introduction to ''Utopia'', trans. Peter K. Marshall (New York: Washington Square Press, 1965), p. xvii.</ref> and hailed More as the father of the Bolshevik Revolution. | ||

<!--T:8--> | |||

Yet More’s Utopian society and Soviet communism have striking differences. For instance, in ''Utopia'', citizenship was dependent upon the belief in a just God who rewards or punishes in an afterlife. | Yet More’s Utopian society and Soviet communism have striking differences. For instance, in ''Utopia'', citizenship was dependent upon the belief in a just God who rewards or punishes in an afterlife. | ||

<!--T:9--> | |||

Professor John Anthony Scott says that More’s “views on communism and private property have been explained as an expression of the medieval monastic ideal, in which Christian men and women took vows of poverty and chastity, shared all things in common, and devoted themselves through prayer and good works to the service of the poor and the sick.”<ref>Ibid., pp. xvii–xviii.</ref> | Professor John Anthony Scott says that More’s “views on communism and private property have been explained as an expression of the medieval monastic ideal, in which Christian men and women took vows of poverty and chastity, shared all things in common, and devoted themselves through prayer and good works to the service of the poor and the sick.”<ref>Ibid., pp. xvii–xviii.</ref> | ||

== See also == | == See also == <!--T:10--> | ||

<!--T:11--> | |||

[[Thomas More]] | [[Thomas More]] | ||

== Sources == | == Sources == <!--T:12--> | ||

<!--T:13--> | |||

{{POWref|25|56}} | {{POWref|25|56}} | ||

<!--T:14--> | |||

{{CAP}} | {{CAP}} | ||

<!--T:15--> | |||

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, ''Saint Germain On Prophecy'', book 2, chapter 17. | Elizabeth Clare Prophet, ''Saint Germain On Prophecy'', book 2, chapter 17. | ||

</translate> | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 20:23, 19 August 2022

Utopia was the principal literary work of Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), published in 1516, a witty exposé of the superficiality of English life and the flagrant vices of English law.

Themes

In his masterpiece, More considers what is the best form of government. He describes an imaginary island, the imaginary commonwealth Utopia (meaning “no place”), where people live according to the rule of reason—free from poverty, crime, and injustice. It is an attempt to depict an ideal society, where neighbor lives in harmony with neighbor and nations are of one accord—not under compulsion of manmade law, but under the wand of grace, the holy will of the Most High.

Influence

Utopia is many things to many people. Historians have taken Utopia as a blueprint for British imperialism, humanists as a manifesto for total reform of the Christian renaissance, and literary critics as a work of a noncommitted intellectual.

In it More describes an ideal society where all property is held in common and food is distributed at public markets and common dining halls. With its sweeping condemnation of all private property, Utopia influenced early Socialist thinkers. Karl Kautsky, the German Socialist theoretician, saw Utopia “as a vision of the socialist society of the future”[1] and hailed More as the father of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Yet More’s Utopian society and Soviet communism have striking differences. For instance, in Utopia, citizenship was dependent upon the belief in a just God who rewards or punishes in an afterlife.

Professor John Anthony Scott says that More’s “views on communism and private property have been explained as an expression of the medieval monastic ideal, in which Christian men and women took vows of poverty and chastity, shared all things in common, and devoted themselves through prayer and good works to the service of the poor and the sick.”[2]

See also

Sources

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 25, no. 56.

El Morya, The Chela and the Path: Keys to Soul Mastery in the Aquarian Age

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Saint Germain On Prophecy, book 2, chapter 17.