Roger Bacon/fi: Difference between revisions

EijaPaatero (talk | contribs) (Created page with "Bacon oli toiminut luennoitsijana Oxfordissa ja Pariisin yliopistossa, mutta nyt hän päättikin irtautua ajatuksineen akateemisen maailman teeskentelevistä ja oletuksia esittävistä asukkaista. Hän etsisi ja löytäisi tieteensä uskonnostaan. Kun hän liittyi fransiskaaniveljeskuntaan, hän sanoi: "Aion tehdä kokeeni, jotka koskevat magneettikiven magneettisia voimia, samassa pyhäkössä, jossa tiedemiestoverini, pyhä Franciscus, suoritti rakkauden magneettisia...") |

EijaPaatero (talk | contribs) (Created page with "== Vaino ==") |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Bacon oli toiminut luennoitsijana Oxfordissa ja Pariisin yliopistossa, mutta nyt hän päättikin irtautua ajatuksineen akateemisen maailman teeskentelevistä ja oletuksia esittävistä asukkaista. Hän etsisi ja löytäisi tieteensä uskonnostaan. Kun hän liittyi fransiskaaniveljeskuntaan, hän sanoi: "Aion tehdä kokeeni, jotka koskevat magneettikiven magneettisia voimia, samassa pyhäkössä, jossa tiedemiestoverini, pyhä Franciscus, suoritti rakkauden magneettisia voimia koskevat kokeensa."<ref>Ed. teos, s. 16.</ref> | Bacon oli toiminut luennoitsijana Oxfordissa ja Pariisin yliopistossa, mutta nyt hän päättikin irtautua ajatuksineen akateemisen maailman teeskentelevistä ja oletuksia esittävistä asukkaista. Hän etsisi ja löytäisi tieteensä uskonnostaan. Kun hän liittyi fransiskaaniveljeskuntaan, hän sanoi: "Aion tehdä kokeeni, jotka koskevat magneettikiven magneettisia voimia, samassa pyhäkössä, jossa tiedemiestoverini, pyhä Franciscus, suoritti rakkauden magneettisia voimia koskevat kokeensa."<ref>Ed. teos, s. 16.</ref> | ||

== | <span id="Persecution"></span> | ||

== Vaino == | |||

But the friar’s scientific and philosophical world view, his bold attacks on the theologians of his day, and his study of alchemy, astrology and magic led to charges of “heresies and novelties,” for which he was imprisoned in 1278 by his fellow Franciscans! They kept him in solitary confinement for fourteen years,<ref>Ibid., p. 17; David Wallechinsky, Amy Wallace, and Irving Wallace, ''The Book of Predictions'' (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1980), p. 346.</ref> releasing him only shortly before his death. Although the clock of this life was run out, his body broken, he knew that his efforts would not be without impact on the future. | But the friar’s scientific and philosophical world view, his bold attacks on the theologians of his day, and his study of alchemy, astrology and magic led to charges of “heresies and novelties,” for which he was imprisoned in 1278 by his fellow Franciscans! They kept him in solitary confinement for fourteen years,<ref>Ibid., p. 17; David Wallechinsky, Amy Wallace, and Irving Wallace, ''The Book of Predictions'' (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1980), p. 346.</ref> releasing him only shortly before his death. Although the clock of this life was run out, his body broken, he knew that his efforts would not be without impact on the future. | ||

Revision as of 09:06, 11 April 2025

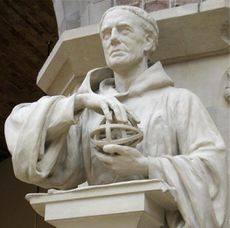

Saint Germain ruumiillistui 1200-luvulla Roger Baconina (n. 1214-1294). Tiedemiehenä, filosofina, munkkina, alkemistina ja profeettana Merlin palaa tehtäväänsä luoda tieteelliset perustukset Vesimiehen aikakaudelle, jota hänen sielunsa jonain päivänä sponsoroisi.

Tieteen profeetta

The atonement of this lifetime was to be the voice crying in the intellectual and scientific wilderness that was medieval Britain. In an era in which either theology or logic or both dictated the parameters of science, he promoted the experimental method, declared his belief that the world was round, and castigated the scholars and scientists of his day for their narrow-mindedness. Thus he is viewed as the forerunner of modern science.

But he was also a prophet of modern technology. Although it is unlikely he did experiments to determine the feasibility of the following inventions, he predicted the hot-air balloon, a flying machine, spectacles, the telescope, microscope, elevator, and mechanically propelled ships and carriages, and wrote of them as if he had actually seen them. Bacon was also the first Westerner to write down the exact directions for making gunpowder, but kept the formula a secret lest it be used to harm anyone. No wonder people thought he was a magician!

On kuitenkin niin, kuten Saint Germain kertoo meille tänä päivänä teoksessaan Alkemian opintoja, että "ihmeet" syntyvät universaalien lakien täsmällisellä soveltamisella. Samoin Roger Bacon tarkoitti ennustustensa osoittavan, että lentokoneet ja maagiset laitteet olisivat luonnonlakien soveltamisen tulosta, minkä ihmiset aikanaan ymmärtäisivät.

Mistä Bacon uskoi saaneensa hämmästyttävän tietämyksensä? "Todellinen tieto ei ole peräisin toisten auktoriteetilta eikä sokeasta uskollisuudesta vanhentuneille dogmeille", hän sanoi. Kaksi Baconin elämäkerran kirjoittajista kirjoittaa, että hän uskoi tiedon "olevan hyvin henkilökohtainen kokemus – valo, joka välittyy vain yksilön sisimmän yksityisyyteen kaiken tiedon ja kaiken ajattelun puolueettomien kanavien kautta."[1]

Bacon oli toiminut luennoitsijana Oxfordissa ja Pariisin yliopistossa, mutta nyt hän päättikin irtautua ajatuksineen akateemisen maailman teeskentelevistä ja oletuksia esittävistä asukkaista. Hän etsisi ja löytäisi tieteensä uskonnostaan. Kun hän liittyi fransiskaaniveljeskuntaan, hän sanoi: "Aion tehdä kokeeni, jotka koskevat magneettikiven magneettisia voimia, samassa pyhäkössä, jossa tiedemiestoverini, pyhä Franciscus, suoritti rakkauden magneettisia voimia koskevat kokeensa."[2]

Vaino

But the friar’s scientific and philosophical world view, his bold attacks on the theologians of his day, and his study of alchemy, astrology and magic led to charges of “heresies and novelties,” for which he was imprisoned in 1278 by his fellow Franciscans! They kept him in solitary confinement for fourteen years,[3] releasing him only shortly before his death. Although the clock of this life was run out, his body broken, he knew that his efforts would not be without impact on the future.

Roger Bacon and astrology

Bacon was a vigorous proponent of astrology. In his day, the words mathematician and astronomer were interchangeable with astrologer. Although astrology flourished in the Middle Ages inside and outside the Church (several popes had court astrologers), it had earlier been condemned by the Church Fathers.

In his Opus Majus Bacon argues that the Church Fathers did not denounce astrology as a whole but rather the fatalism of some practitioners. According to Bacon, the problem exists in “lying or fraudulent mathematicians, full of superstition,” who “imagine that necessity is placed upon those things in which there is choice, and particularly in matters which proceed from free will.”[4] In other words, those who claim that astrology is predestination are misusing it.

He says that on the other hand “true mathematicians and astronomers or astrologers, who are philosophers, do not assert a necessity and an infallible judgment in matters contingent on the future.”[5]

Legacy

The following prophecy which he gave his students shows the grand and revolutionary ideals of the indomitable spirit of this living flame of freedom—the immortal spokesman for our scientific, religious and political liberties:

I believe that humanity shall accept as an axiom for its conduct the principle for which I have laid down my life—the right to investigate. It is the credo of free men—this opportunity to try, this privilege to err, this courage to experiment anew. We scientists of the human spirit shall experiment, experiment, ever experiment. Through centuries of trial and error, through agonies of research ... let us experiment with laws and customs, with money systems and governments, until we chart the one true course—until we find the majesty of our proper orbit as the planets above have found theirs.... And then at last we shall move all together in the harmony of our spheres under the great impulse of a single creation—one unity, one system, one design.[6]

See also

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Lords of the Seven Rays

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Astrology of the Four Horsemen

- ↑ Henry Thomas and Dana Lee Thomas, Living Biographies of Great Scientists (Garden City, N.Y.: Nelson Doubleday, 1941), s. 15.

- ↑ Ed. teos, s. 16.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 17; David Wallechinsky, Amy Wallace, and Irving Wallace, The Book of Predictions (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1980), p. 346.

- ↑ The Opus Majus of Roger Bacon, trans. Robert Belle Burke, vol. 1 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1928), p. 268.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Thomas, Living Biographies, p. 20.