Útópía - Fyrirmyndarríkið

„Útópía“ var helsta bókmenntaverk Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), gefið út árið 1516, skondin afhjúpun á yfirborðsmennsku ensks lífs og augljósum lesti enskra laga.

Stef

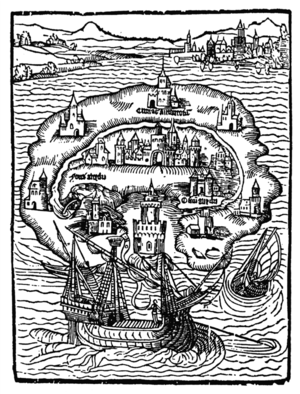

Í meistaraverki sínu veltir Meira fyrir sér hvaða stjórnarfar sé best. Hann lýsir ímyndaðri eyju, ímyndaða samveldisútópíu (sem þýðir „staðleysa“), þar sem fólk lifir samkvæmt reglu skynseminnar – laust við fátækt, glæpi og óréttlæti. Þetta er tilraun til að lýsa fyrirmyndarsamfélagi, þar sem nágranni lifir í sátt við náunga sinn og þjóðir eru sammála – ekki undir nauðung manngerðra laga, heldur undir náðarsprota, heilögum vilja hins hæsta.

Influence

Utopia is many things to many people. Historians have taken Utopia as a blueprint for British imperialism, humanists as a manifesto for total reform of the Christian renaissance, and literary critics as a work of a noncommitted intellectual.

In it More describes an ideal society where all property is held in common and food is distributed at public markets and common dining halls. With its sweeping condemnation of all private property, Utopia influenced early Socialist thinkers. Karl Kautsky, the German Socialist theoretician, saw Utopia “as a vision of the socialist society of the future”[1] and hailed More as the father of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Yet More’s Utopian society and Soviet communism have striking differences. For instance, in Utopia, citizenship was dependent upon the belief in a just God who rewards or punishes in an afterlife.

Professor John Anthony Scott says that More’s “views on communism and private property have been explained as an expression of the medieval monastic ideal, in which Christian men and women took vows of poverty and chastity, shared all things in common, and devoted themselves through prayer and good works to the service of the poor and the sick.”[2]

See also

Sources

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 25, no. 56.

El Morya, The Chela and the Path: Keys to Soul Mastery in the Aquarian Age

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Saint Germain On Prophecy, book 2, chapter 17.