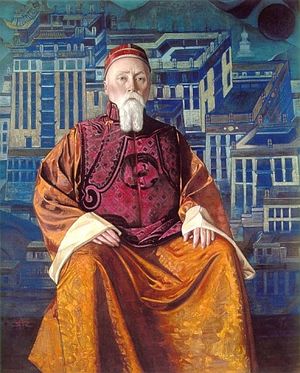

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich was a world-renowned artist, archaeologist, author, scholar, lecturer, costume and set designer, poet, mystic and explorer. He and his wife, Helena Roerich, served during the early twentieth century as amanuenses for the ascended masters El Morya and Maitreya. Nicholas ascended at the conclusion of that lifetime.

Early life

He was born in St. Petersburg on October 9, 1874, the firstborn son of Konstantin and Maria Roerich. The name Nicholas means “one who overcomes,” and Roerich means “rich in glory.” His father was a prominent attorney and notary, and Nicholas spent much of his youth at the family’s large country estate, Isvara, located about fifty-five miles southwest of St. Petersburg. There in the beauty of northern Russia a lifelong love for nature was kindled in young Nicholas. At Isvara he developed a passion for hunting and an avid interest in natural history, archaeology and the history of Russia. He was fond of music and horseback riding.

His father wanted him to study law, but Nicholas wanted to pursue art. Nicholas resolved the situation by enrolling simultaneously in the law faculty of the Imperial University and the Imperial Academy of Arts.

In 1898 Nicholas became assistant director of the museum of the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. In September 1900 he went to Paris to study art. In the summer of 1901, Nicholas returned to St. Petersburg and in October married Helena Ivanovna Shaposhnikova. Helena was an accomplished pianist and came to be regarded as a distinguished lady of letters and a prolific writer in the esoteric tradition of Eastern religion. She was his twin flame, an inspiration and support to Nicholas throughout his life. Nicholas and Helena had two sons, George and Svetoslav.

In the early 1900s, the Roerichs traveled extensively throughout Russia and Europe. During these journeys, Professor Roerich painted, undertook archaeological excavations, studied architecture, lectured and wrote about art and archaeology. In 1906 he was promoted from secretary to director of the school of the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts.

In 1907 he began applying his talents to stage and costume design. This became a fulfilling and successful career for Roerich. He designed sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s ballet and opera productions, including Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, and for almost all of Wagner’s and many of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas.

The Roerich family left Russia for Finland in 1918, shortly before the border between Finland and the Soviet Union was permanently closed. At the invitation of the director of the Chicago Art Institute, Roerich came to the United States in 1920. He traveled widely, lectured and exhibited his works. While in the United States, Roerich founded the Master Institute of United Arts, an international society of artists called Cor Ardens (which means “Flaming Heart”), and an international art center in New York called Corona Mundi (which means “Crown of the World”). As a tribute to Roerich, the Roerich Museum was established in New York in 1923.

Artwork

Many of Roerich’s works are magnificent scenes of nature, and his themes are inspired by history, architecture and religion. His paintings are mystical, allegorical and even prophetic. Between 1912 and 1914, his paintings often reflected a sense of impending cataclysm. One of these, The Last Angel (1912), depicts an intense conflagration enveloping a city; above the city, surrounded by billowing clouds of smoke, an angel bearing a sword and shield heralds the Final Judgment. In 1936, just before World War II, Roerich painted Armageddon. One can see the rooftops of a city visible through clouds of smoke with the silhouettes of soldiers marching in the foreground across the bottom of the picture.

Roerich’s artistic style is difficult to describe because, as Claude Bragdon put it, he belongs to an elect fraternity of artists—including da Vinci, Rembrandt, Blake and, in music, Beethoven—whose works have “a unique, profound and indeed a mystical quality which differentiates them from their contemporaries, making it impossible to classify them in any known category or to ally them with any school, because they resemble themselves only—and one another, like some spaceless and timeless order of initiates.”[1]

Journey to the East

Nicholas Roerich was greatly influenced by Eastern culture. He had desired for a long time to travel to the East in order to study the ancient culture firsthand, and in 1923 he set sail for India. He resided for a time in Sikkim (then a kingdom bordering northeast India) while making final plans for an expedition to Central Asia. Roerich wrote of his enchantment with the mountains:

All teachers journeyed to the mountains. The highest knowledge, the most inspired songs, the most superb sounds and colours are created on the mountains. On the highest mountains there is the Supreme. The high mountains stand as witnesses of the great reality.[2]

Himalayas! Here is the Abode of Rishis. Here resounded the sacred Flute of Krishna. Here thundered the Blessed Gautama Buddha. Here originated all Vedas. Here lived Pandavas. Here—Gesar Khan. Here—Aryavarta. Here is Shambhala. Himalayas—Jewel of India. Himalayas—Treasure of the World. Himalayas—the sacred Symbol of Ascent.[3]

Both Nicholas and Helena Roerich had an intense interest in Eastern philosophy and religion. Many of his paintings contain both Western and Eastern deities, saints and sages. His series “Banners of the East” portrays not only spiritual leaders of the past but the hopes of the East for a coming leader. Roerich captured these hopes in his paintings of Maitreya and the World Mother.

In 1925 Roerich started on his Central Asian expedition with Helena, his son George and several other Europeans. Roerich wrote of his goals:

Of course, as an artist my main aspiration in Asia was towards artistic work.... In addition to its artistic aims, our Expedition planned to study the position of the ancient monuments of Central Asia, to observe the present condition of religions and creeds, and to note the traces of the great migrations of nations.[4]

Roerich’s party traveled 15,500 miles through Central Asia in an arduous and often dangerous trek that took more than four years. Despite overwhelming obstacles, Roerich executed hundreds of paintings during the journey.

While on this expedition, Roerich discovered legends and manuscripts recounting the journey Jesus took to the East during his so-called lost years between the ages of twelve and thirty. The same or similar manuscripts were also found by Russian journalist Nicolas Notovitch and Swami Abhedananda at Himis monastery in Ladakh.[5]

At the conclusion of the Central Asian expedition in 1928, the Roerichs permanently settled in the Kulu Valley in India. There they founded the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute to study archaeology, linguistics and botany.

The Banner of Peace

One of the goals of Roerich’s lifelong pursuit of preserving the world’s cultural heritage came to fruition in 1935 with the signing of the Roerich Pact treaty at the White House by representatives of the countries comprising the Pan-American Union. Under the pact, nations at war were obliged to respect museums, universities, cathedrals and libraries as they did hospitals. Just as hospitals flew the Red Cross flag, cultural institutions would fly Roerich’s “Banner of Peace,” a flag that has a white field with three red spheres in the center surrounded by a red circle. Roerich believed that by protecting culture, the spiritual health of the nations would be preserved.

Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1929 and 1935 for his efforts to promote international peace through art and culture and to protect art treasures in time of war. World War II interrupted his activities and those of the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, and Roerich devoted himself to helping victims of the war. He also donated money from the sale of his paintings and books to the Soviet Red Cross.

In the summer of 1947, Roerich had heart surgery but was soon back at his easel. One of the last works Roerich painted is called The Master’s Command. It depicts a white eagle flying toward a devotee who is meditating in the lotus posture atop a high cliff overlooking a mountain valley. On December 13, 1947, while Roerich was working on a variant of this picture, his heart suddenly failed and his soul took flight to higher octaves. He was seventy-three years old.

Legacy

Throughout his life, Nicholas Roerich found the time to be involved in a multitude of activities and to do them all well. His spiritual life was the wellspring from which his literary and artistic vision arose. In an article about the character and work of his father, Svetoslav Roerich summed up the artist’s quest for inner spirituality:

He was a great patriot and he loved his Motherland, yet he belonged to the entire world and the whole world was his field of activity. Every race of men was to him a brotherly race, every country a place of special interest and of special significance. Every religion was a path to the Ultimate and to him life meant the great gates leading into the Future.... Every effort of his was directed towards the realisation of the Beautiful and his thoughts found a masterful embodiment in his paintings, writings and public life....

Through all his paintings and writings runs the continuous thread of a great message—the message of the Teacher calling to the disciples to awaken and strive towards a new life, a better life, a life of beauty and fulfillment.[6]

His service as an ascended master

The ascended master Nicholas Roerich says:

I am grateful to address you today, to speak to you from the plane of the ascended masters that you might know that one from among you has graduated to this level and that you might accomplish the same. Never tire, then, in the work that is your dharma, your duty to be the wholeness of yourself. Never be frustrated that you are misunderstood or before your time in your understanding of the stars, the universes, the mountains and the petals of a flower. I have indeed fought the good fight, and I have won.[7]

He asks us to call to him, and he stresses the use of the violet flame:

I ask you, chelas of the ascended masters, to include my name in your decrees and preambles, as I work closely with El Morya, K.H. and D.K., and Lanello. I work closely with them for the bringing together of all those who are on the path of the sacred fire.[8]

For more information

For more information about Nicholas Roerich and his magnificent artwork, see the website of the Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, www.roerich.org.

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Nicholas Roerich.”

- ↑ Claude Bragdon, Introduction, in Nicholas Roerich, Altai-Himalaya: A Travel Diary (Brookfield, Conn.: Arun Press, 1929), p. xix.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Himalayas: Abode of Light (Bombay: Nalanda Publications, 1947), p. 21, in Jacqueline Decter, Nicholas Roerich: The Life and Art of a Russian Master (Rochester, Vt.: Park Street Press, 1989), p. 141.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Himalayas, p. 13, in Decter, Nicholas Roerich, p. 203.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Heart of Asia (New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1929), pp. 7, 8.

- ↑ Roerich, Notovotch and Abhedananda all published their translations of these texts describing Jesus’ journey to the East. All three accounts are included in Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus’ 17-Year Journey to the East.

- ↑ Svetoslav Roerich, “My Father,” in Nicholas Roerich (New York: Nicholas Roerich Museum, 1974), p. 15.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, “Be the Unextinguishable Ones!” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 33, no. 44, November 11, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid.