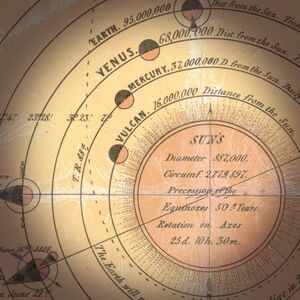

Vulcan (planet)

Vulcan is a planet that is closer to the sun than Mercury. There isn’t any scientific evidence for it, but H. P. Blavatsky mentions it in The Secret Doctrine.[1] Astrologers have named it. Some modern astronomers believed that it existed and were trying to determine its orbit, which would be so close to the sun that it would be extremely difficult to observe.[2] On the basis of that information we could conclude that there is a grid and forcefield of energy near the sun which needs to be dealt with.

There is a chemistry to each planet, to its electronic belt. Each planet has a divine plan and it has a divine purpose. Its evolution sometimes throughout the aeons has perverted that purpose, and that perversion remains as a forcefield on that planet. When that perverted forcefield comes in contact and mixes with the hierarchy of the Sun with which the planet is associated, there is another chemistry, which is the interaction of the electronic belt of the planet with all universal misuses of that sun sign.

See also

For the cosmic being Vulcan, see Vulcan, God of Fire

Sources

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, October 7, 1976.

- ↑ H. P. Blavatsky writes in The Secret Doctrine, “Many more planets are enumerated in the Secret Books than in modern astronomical works” (vol. 1, p. 152). She specifically refers to “an invisible intra-Mercurial planet ... one of the most secret and highest planets. It is said to have become invisible at the close of the Third Race” (vol. III, pp. 459, 462). She elsewhere referred to 19th century astronomers who claimed to have seen this planet and named it Vulcan (Transactions of the Blavatsky Lodge, p. 48).

- ↑ Speculation about a planet closer to the sun than Mercury dates back to the 17th century. Support for its existence grew in the 19th century when astronomers observed anomalies in the orbit of the planet Mercury. Mathematician Urbain Le Verrier tried to explain these within the framework of Newtonian physics by proposing the existence of a hitherto unknown planet within the orbit of Mercury, publishing his findings in 1859. (Le Verrier had earlier predicted the existence of the planet Neptune using disturbances in the orbit of the planet Uranus, lending credibility to his theory.) An amateur astronomer, Edmond Modeste Lescarbault, claimed to have seen this planet, and on January 2, 1860, Le Verrier announced the discovery at the Academie des Sciences in Paris, proposing the name “Vulcan.” Lescarbault was awarded the Légion d’honneur for this discovery, and astronomers continued the search for Vulcan over the following decades, with numerous sightings, some by prominent astronomers. In its August 31, 1878, issue, Scientific American stated with some confidence that the planet Vulcan “will probably now have to be admitted to full standing among the planets.” However, Einstein’s 1915 theory of general relativity explained the anomalies in the orbit of Mercury without requiring another planet, effectively ending the scientific search. Today, the International Astronomical Union has reserved the name “Vulcan” for the “hypothetical” planet inside the orbit of Mercury.